For well over a millennium Muslims have revered Mecca as the site of their holiest shrine, the Kaaba. And until recently Western scholarship always accepted the traditional Muslim origins narrative, which says that was where Muhammad began, in Arabia. But in the late 1970s, John Wansbrough and two of his students, Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, published books arguing for a radically different approach to Islam’s origins.[1]

Among other things, these revisionists said that Mecca was not Islam’s birthplace, which they located somewhere in the Fertile Crescent. Though Crone and Cook later repudiated the theory their book advanced, Crone at least held fast to the idea that Islam originated in the Fertile Crescent, possibly in Nabatea.

While the trend among Western scholars of Islam is away from such radical doubt, four decades later some scholars still promote the idea that the Kaaba was not originally in Mecca.

Some of these revisionists say it was in or near Petra, while others refuse to speculate on the exact location. And this notion has begun to trickle down to others in the West, through the work of popular historian and documentary filmmaker Tom Holland, for example. Filmmaker and writer Dan Gibson has also promoted the idea widely.[2] Since Muslims pray facing Mecca’s Kaaba multiple times a day, one thing this view would mean is that Muslims everywhere naively face the wrong direction in their most frequent act of worship.

Revisionists variously claim the following evidence supports their theory:

- The qur’anic data

- Other early written evidence

- The hadith’s data on Mecca

- The archaeological record

- Al-Tabari’s historical record

- Mecca’s geographic conditions

It’s important to recognize that ancient history rarely offers the absolute proof of an airtight case. Instead, we must base our conclusion on the preponderance of the evidence.

Besides these six lines of evidence, we must also consider how plausible it is that the early Muslim community reassigned its origins to a different city than that of its actual birthplace. Most revisionists allege that Muslims made this change during Islam’s classical period for political reasons. Yet how believable is it that Islam originated not in Mecca, but in Petra or somewhere else in Nabatea?

1. The qur’anic data

Regarding the qur’anic evidence, the fact that the Qur’an names Mecca just once[3] may look suspicious when compared with the New Testament’s naming Jerusalem, for example, almost 180 times. However, the two scriptures are radically different books. By way of comparison, the Qur’an names only a few contemporary geographic locations and none more than a couple of times, while the New Testament names many towns and other geographic features multiple times. Likewise, the Qur’an names Muhammad just four times, while the New Testament uses the name Jesus well over a thousand times. Thus, the important point with reference to the Qur’an’s naming of Mecca is that it names it in relation to its own story,[4] whereas Petra (al-Raqim) is mentioned only in relation to a historical event.[5] And there’s nothing about that mention to suggest that al-Raqim is in the vicinity of Muhammad’s hearers.

Some scholars think other qur’anic data point to Islam’s having originated in Nabatea. They cite

- Sodom’s location in relation to Muhammad’s hearers

- Animals mentioned in the Qur’an

- Fruits mentioned in the Qur’an

But much here depends on how we interpret the text. A literal reading of Q 37:137 locates Muhammad’s hearers close enough to Sodom’s Nabatean ruins that they passed by them twice daily. (But even Petra is ruled out by a literal reading since Petra is some 80 kilometers or 50 miles distant from the south end of the Dead Sea, where Sodom’s ruins are supposed to lie. And a return journey of that distance wasn’t been possible back then.) A freer reading allows for the traditional interpretation. It puts those ruins in the vicinity of a caravan route to Syria many of Muhammad’s hearers would have been familiar with.

Q 80:24-32 and other Meccan passages speak of God’s provision of fruit and anʿām—sometimes translated “cattle”—which Mecca’s climate would not have allowed. But anʿām can also be translated “beasts,” which could mean camels. This would make the verse’s provisions “for you and your beasts” relevant to traders and camel herders alike. Q 6:136-139 implies that Muhammad’s opponents were themselves farmers. But such passages may well detail practices of residents of pagan Ta’if, just 87 kilometers (54 miles) from Mecca. In fact, most of the Qur’an’s agricultural references require a locale no further afield than Ta’if, famous for its grapes, pomegranates, figs, etc. Only olives would require the growing conditions found in Yemen and Nabatea-Palestine, at either end of western Arabia’s overland trade route. Thus, almost everything in the Qur’an’s early suras is compatible with its Hijazi origins. There is also no reason to reject the traditional Muslim view that these texts speak universally (possibly after the pattern of the biblical psalms[6]).

Revisionists must reckon with two other facts which argue against Islam’s Nabatean origins:

- The presence of 200 Amharic and Ethiopic loanwords in the Qur’an[7]

- Qur’anic references to pagans’ idol worship and animal sacrifice

Significant linguistic borrowing suggests extensive cross-cultural interaction. When goods and ideas are exchanged, words often are as well. Cultural dominance may play into linguistic borrowing also, and Ethiopia ruled the Hijaz for a time during the 6th century. If the Qur’an’s early suras were addressed to the inhabitants of Petra, one might expect more Coptic than Amharic and Ethiopic loanwords since Nabatea was much closer culturally to Egypt than to Ethiopia. Yet Amharic and Ethiopic words in the Qur’an stand in a 20:1 ratio to Coptic words.[8] While this simple numerical comparison is not conclusive, it certainly raises questions.

Regarding pagan practices, the Byzantines had forbidden both idol worship and animal sacrifice long before Muhammad’s time—including in their province of Arabia Petraea.[9] Yet the Qur’an repeatedly refers to idolatry as a contemporary practice, calling the unbelievers to forsake their idols, which they look to for protection (e.g., Q 2:256-57, 16:36). G.R. Hawting has argued that Muhammad challenged only the “spiritual idolatry” of retrograde monotheists.[10] But in its listing of proscribed foods, Q 5:3 says, “Forbidden to you are carrion, blood, pork… whatever has been sacrificed to idols.” This was clearly pagan idolatry, which points to a region like Arabia’s Hijaz, beyond the bounds of the Byzantine Empire. Q 22:30 also warns against contamination by “the filth of idols” (awathan). The Qur’an also condemns “sacrificial stones” and the meat sacrificed on them (Q 5:3, 5:90). But since sacrifice had long ceased to be part of Jewish practice and was never practiced by Christians, this can only relate to idolatrous practice. The Qur’an repeatedly bans “that on which any name other than God has been invoked” (e.g., Q 2:173, 5:3). Likewise, Abraham is repeatedly presented as the prophetic hero who challenged his people’s idolatry (e.g., Q 26:69-102) as Muhammad is now doing.

How does such paganism square with the Qur’an’s mention of the idolaters’ belief that God (Allah) created the world? In fact, it’s consonant with what we know of widespread polytheistic belief in a High God.[11] Q 6:136 even describes the pagans as offering some portion of their produce to God, while other passages present them as ascribing offspring to God, swearing by God and even praying to God when in distress (e.g., 6:63-64, 6:109, 16:57). Not only is this qur’anic picture of pre-Islamic paganism consonant with polytheistic belief in a High God. It’s also generally consistent with both pre-Islamic poetry and the Book of Idols. And epigraphic evidence from both Palmyra and South Arabia attests to the pre-Islamic Arabs’ ascription of daughters to God. To sum up, the Qur’an condemns not adulterated monotheism, but rather literal idolatrous polytheism, something that had by the early seventh century been long forbidden in Byzantine Nabatea.[12]

Thus, the Qur’an’s mention of Mecca, its Ethiopic loanwords, and its references to idolatrous practice all make the Hijaz a location more likely for Islam’s emergence than Nabatea.

2. Other early written evidence

Some scholars believe the lateness of the earliest written extra-qur’anic evidence for Mecca renders it unreliable. Revisionists clearly reject the idea that Ptolemy included Mecca, as “Makoraba,” on his second century CE map of Arabia. That question is of relatively minor import. But regardless, they thus conclude that the first map documenting Mecca’s existence is late.

Regarding textual evidence, only a small percentage survives from any ancient culture. And unlike the Mediterranean world at the time of Christ, Arab culture was oral during Islam’s first two centuries, producing little written Arabic before the ninth century, beyond inscriptions, graffiti, business and administrative records, and the Qur’an. Hence, the earliest extra-qur’anic Arabic mention of Mecca comes from the late seventh century, with most of the early mentions being from the late eighth century. However, wishing we had earlier evidence doesn’t license us to discount the early Arabic evidence we do have. And all the early written accounts of Islam’s origins point to Mecca, none to Petra or Nabatea..[13]

3. The hadith’s data on Mecca

We should take hadith descriptions of Mecca’s grandeur and lush vegetation as hyperbole designed to glorify Mecca, like the Qur’an’s designation of its home base as the “Mother of Settlements” (Q 6:92, 42:5). Crone is doubtless right to argue that western Arabia’s economy was unable to support the populations mentioned in the hadith.[14] Neither was Mecca on a major trade route. But again, we should not allow the Qur’an’s hyperbolic designation or the hadith’s hyperbolic elaborations to mislead us into looking for a large city at the nexus of a trade empire.

Hadith sources consistently disagree when hyperbolizing. It is where they consistently agree that we should pay attention. And they invariably make Mecca Islam’s birthplace.

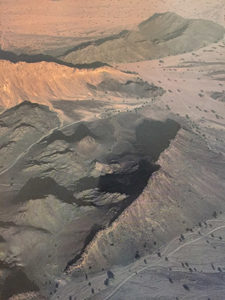

4. The archaeological record

Revisionists make two claims about the archaeological record. They claim that

- There’s no archaeological evidence that Mecca was inhabited in the seventh century

- The qibla, or prayer direction, of most of Islam’s early mosques points to Petra, not Mecca

Due to the Saudi Arabian government’s mortal dread of shirk, or polytheism, it has strictly forbidden all archaeological study of Mecca’s historic sites, lest it lead to relic worship. Indeed, the Saudis seem determined virtually to obliterate the city’s archaeological record in their rush to ring the Kaaba with skyscrapers. An estimated 95% of Mecca’s historic buildings have been demolished to allow for this building spree. Any remaining historic sites are treated with a combination of fear, contempt and scholarly avoidance, lest they be idolized.[15]

Unfortunately, this leaves us with no archaeological evidence either for or against Mecca’s being Islam’s birthplace.

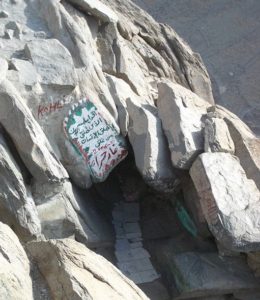

The other archaeological claim some revisionists make relates to early mosque orientation. Following Crone, writer and documentary filmmaker Dan Gibson claims close agreement in the qibla, or prayer direction, of most of Islam’s early mosques—but to Petra, not Mecca.[16] Some enthusiasts of Gibson’s view claim that the reliability of his assertions is easily demonstrated simply by using the satellite imagery of early mosques accessible through Google Earth. But any confirmation this tool yields is unreliable due to the fact that many early mosques have multiple foundations, representing various qibla orientations. In other words, we can prove each ancient mosque’s original orientation only by conducting a thorough archeological study of it, digging down to its original foundation. While Crone quickly accepted this correction, Gibson has not yet done so.

The level of qibla agreement Gibson claims to have found is also impossible for a number of reasons. To begin, their builders used conflicting methods to determine the qibla, just as American Muslims do today.[17] Reflecting these conflicting methods, the mosques they built do not agree, though all their builders did their best to orient them to Mecca. In addition, the early Muslims had a very basic understanding of geography. As Islamic science historian David A. King explains, “The first generations of Muslims had no means whatsoever for finding the direction of Petra [or Mecca either] accurately to within a degree or two, not least because they had no access to any geographical coordinates, let alone modern ones, and no mathematics whatsoever.” The early Muslims determined the qibla accurately by the standards of the day, using the best folklore-based methods at their disposal.[18]

But with only primitive astronomy and maps and no mathematics, they were unable to achieve anything close to modern-day accuracy.[19] Thus, while the early Muslims oriented their mosques toward Mecca, their limited abilities and conflicting methodologies makes this far from self-evident.

5. Al-Tabari’s historical record

Reading between the lines, Gibson suggests that al-Tabari’s account of Ibn al-Zubayr’s trip to Mecca in 70 AH (689-90 CE) may point to the Muslim community’s relocation from Petra to Mecca.[20] Tabari says Ibn al-Zubayr took “many horses and camels and much baggage” with him to Mecca. But had the rebel Ibn al-Zubayr’s trip represented a communal move and a relocation of the Black Stone to Mecca, why would his enemies not have reversed it upon his defeat? As for the horses mentioned, he would have needed them to mount the defense of his chosen refuge. Ibn al-Zubayr needed the money since transferring power from Damascus involved outfitting and rewarding his supporters, and money (all coins) was heavy in those days. Tabari also says that many camels were slaughtered on his arrival in Mecca—doubtless to celebrate his victory, fleeting though it was. There’s nothing to suggest that this points to the Muslim community’s relocation of Islam’s holiest shrine.[21] And while Tabari never once mentions Petra, he elsewhere repeatedly names Mecca as home of the Kaaba.

6. Mecca’s geographic conditions

Some argue that Mecca’s harsh conditions and geographic isolation make it a wretched choice for the spiritual center of the world.[22] But Muhammad never claimed to choose Mecca, but rather that Mecca chose him. And however ambitious he was, it seems likely that he initially hoped to make his hometown simply the center of his Arabian theocracy. When he first began, he could not have known how much of the globe his armies would subdue.

7. The question of plausibility

The last issue for us to consider in assessing the theory that Petra or some other city in the Fertile Crescent is Islam’s real birthplace is that of the plausibility. That is, how plausible is the move the theory necessitates from Islam’s alleged birthplace to Mecca?

Specifically, how could the Muslim community have seamlessly made and accepted the move from Islam’s “real birthplace” to Mecca, its “pseudo-birthplace,” without leaving any trace of that move in the written record?

Of the proposed answers to this question, two call for our consideration. They are that

- Muslims called Petra “Mecca” prior to the alleged move

- The early Muslims determined to cover their tracks

Gibson puts forward the hypothesis that Muslims formerly called Petra “Mecca,” a hypothesis endorsed by Christian apologist Jay Smith. This would mean there were two Meccas, the first being Petra, the second being the Kaaba’s current home in Saudi Arabia. Thus, when the Qur’an names Mecca, it’s referring to the original Mecca—that is, Petra. Likewise, the hadith accurately describe the Nabatean “Mecca” before the Muslim community gave the Kaaba’s new Hijazi home the same name. What evidence does Gibson have to support his claim that “Mecca” originally referred to Petra? He bases it on the testimony of a 9th-10th century Christian historian named Thomas Artsruni. He wrote that Muhammad had preached in Mecca, located in “Arabia Petraea Paran.” According to Gibson, Thomas locates Mecca in Petra, “in southern Jordan.”[23]

However, Thomas locates Mecca, not in the city of Petra at all, but only in the Byzantine province of Arabia Petraea, specifically in its Paran, or Sinai, region. Two things explain Thomas’s mistake. First, he wrote in his native Armenia and wrote of distant places he’d never seen. Second, he likely placed Mecca in Paran because Muslims claim that Mecca was the site of Hagar and Ishmael’s exile, an event Genesis 21:22 locates in Paran. In other words, Thomas mistakenly assumed that Mecca must be in Paran since the author of Genesis set Hagar and Ishmael’s story there.[24] Thus, we should overlook Thomas’s error, not build on it.

The other explanation for the hadith’s total silence on the topic of the Muslim community’s alleged move of its central shrine is that the early Muslims determined to cover their tracks. They wanted their move of the qibla quickly forgotten, lest it diminish Mecca’s sanctity and legitimacy. But the realities of the period in which the alleged move occurred argue strongly against the hadith’s complete failure to mention it:

- The Muslim community was widely distributed within a few years of Muhammad’s death in 632 CE.

- The community was deeply divided from that point on, with Sunni, Shia, Khariji and other Muslim groups fighting to gain or hold onto power.

- The alleged change of qibla would have been a matter of paramount importance since Muslims have always worshipped in a single prescribed direction.

- The hadith reflect the early Muslim community’s regional, sectarian and other divisions and disagreements in numerous respects.[25]

Yet, despite the community’s broad geographic distribution and deep division and the central importance of the qibla, the hadith register no disagreement whatsoever on this point. To think that so sprawling and so unruly a community could either unanimously agree to relocate its sacred center or somehow manage to do so without leaving a single trace of the move in the hadith record is highly implausible to say the least.

To sum up, ancient history seldom offers the sort of proof that enables us to build an airtight case. Thus, we can only carefully weigh all the evidence and decide which conclusion most of the best evidence supports. As I have shown here, none of the six lines of evidence revisionists use to support their view is compelling. Instead, the preponderance of the evidence points to Mecca as Islam’s true birthplace. That is especially true when we allow that oral history—like that later recorded in the hadith—is not inherently false and consider the implausibility of the alleged relocation of the Kaaba.

Hence, contrary to what most revisionists claim, we can affirm with reasonable confidence that Muslims do not mistakenly face the wrong direction when they pray.

[1] Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977) 23-24, John Wansbrough, Qur’anic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977). Other Western scholars had previously questioned the hadith basis of the traditional origins story, but Wansbrough, Cook and Crone can be credited with beginning Islamic revisionism as a school of thought.

[2] Tom Holland, In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire (New York: Doubleday, 2012) and the film Islam: The Untold Story. Dan Gibson, The Sacred City: Discovering the Real Birthplace of Islam (Glasshouse Media, 2017); also Qur’anic Geography (Surrey, BC: Independent Scholars Press, 2011).

[3] It also names Becca—said to be an alias for Mecca—as the site of Abraham’s sacred house, the Kaaba.

[4] Though the Qur’an never tells its story in any detailed chronological fashion, it frequently alludes to events and infrequently names places in it also. The fact that Mecca is one of the few places named in that context is highly significant.

[5] Mehdy Shaddel argues convincingly that “al-Raqim” in Q 18:9 is actually the Arabic name for Petra, “Studia Onomastica Coranica: al-Raqīm, Caput Nabataeae” in Journal of Semitic Studies 42: 303-18.

[6] Angelika Neuwirth, “Qur’anic Reading of the Psalms,” in The Qur’an in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qur’anic Milieu, ed. Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai and Michael Marx (Leiden: Brill, 2010) 733-78.

[7] Arthur Jeffery, The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur’an (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1938).

[8] Aramaic and Syriac, on the other hand, exerted a major influence on the entire region, even far-off Yemen.

[9] Nicolai Sinai, The Qur’an: A historical-critical introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017) 61.

[10] G.R. Hawting, The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[11] Passages like Q 27:91, 28:57, 29:67 and 106:3 say that Mecca’s pagans considered God (Allah) the Lord of the Kaaba or of Mecca. But according to the Book of Idols, the pagans considered Hubal the Lord of the Kaaba.

[12] Nicolai Sinai, The Qur’an: A historical-critical introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017) 66-72.

[13] See pp. 9-10 below for my treatment of the 9th-10th century testimony of Thomas Artsruni.

[14] Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2004).

[15] One example of this fear and contempt is that the house of Khadija, Muhammad’s first wife, has been turned into a block of toilets. Likewise, while radical clerics have repeatedly called for the demolition of the house in which Muhammad was born, the Saudis have used it as a cattle market for many years. Ziauddin Sardar, Mecca: The Sacred City (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014) 346-47.

[16] Gibson claims the exceptions face halfway between Petra and Mecca. Missing in both Gibson’s book and film is precise archaeological evidence for each of the mosques studied. And no amount of cinematic wizardry can make up for this lack. Qur’anic Geography and The Sacred City: Discovering the Real Birthplace of Islam.

[17] Many American mosques face southeast, based on Mecca’s direction on a flat map, while others face northeast, based on the shortest distance around the globe.

[18] http://www.muslimheritage.com/article/from-petra-back-to-makkaarticles Accessed July 8, 2018. King has written numerous articles and books on early qibla determination.

[19] Hence, the only explanation for any early mosques accurately oriented toward either Petra or Mecca—if, indeed, any exist—is coincidence.

[20] Gibson, The Sacred City.

[21] https://archive.org/stream/TabariEnglish/Tabari_Volume_21#page/n9/mode/2up Accessed July 8, 2018.

[22] Most revisionists hypothesize that the early Muslims relocated Islam’s center to Mecca for its remoteness, in order to make the Kaaba (with its vital Black Stone) immune to political intrigue. But it is not hard to imagine every rebel spiriting the stone off and rebuilding its shrine in his preferred location. That did not happen in all the centuries since the stone was allegedly moved to Mecca because it is precisely Mecca’s Muhammadan history that sanctifies it to Muslims.

[23] Gibson, “Petra in the Qur’an,” 14. http://thesacredcity.ca/Petra%20In%20The%20Qur%27an.pdf Accessed September 14, 2018.

[24] Gibson’s presupposition that the original Kaaba was in Petra led him to see Thomas as explaining why Muslim accounts always named Mecca, never Petra, as Islam’s birthplace—or as he sees it, “why Petra is continually referred to as Mecca in the Islamic accounts”; Gibson, “Petra in the Qur’an,” 14. But even supposing that Muslims used the name Mecca for Petra before relocating the Black Stone to the Hijazi Mecca, this does not explain why they never again referred to Petra as Mecca (or “Old Mecca”) after that historic move.

[25] Even if every Muslim alive at the time of the alleged move vowed to keep it secret, how likely is it that the next generation of Muslims would not have leaked multiple versions of the story into the hadith?

Hello I was thinking about Q 37:137-138 recently and to me the idea that it is explained by caravans to the Syria/Palestine doesn’t seem to fit the verse. It says “Surely you indeed pass near them [the ruins of the town/city of the people of Lot] in the mourning and in the night. Will you not understand?”. This to me seems to indicate that the audience is regularly passing by the ruins which would indicate vicinity to the location of the Sura’s composition and audience (and serve as a warning to them by God). However I agree with you that it probably was composed in Mecca (or in the area of Mecca) because the other hypotheses (like the Petra one) cause much more problems than they solve. So I think in order to reconcile this we need to think outside the box. Maybe the Quran instead just has a different geographic location in mind for the city of Lot. This would solve a lot of problems while at the same time explain the curious lack of sulfur and salt in the Quranic story of the destruction of the city of Lot. In the Quran the city/town is destroyed by a rain of “stones of baked clay, one after another” rather than fire and sulfur like in Genesis. And Lot’s wife is just left behind and killed in the rain of stones along with everyone else in the city/town. She is not turned into a pillar of salt like in Genesis. If the Quranic audience thought the town of Lot was in the southern Dead Sea area like the Biblical tradition says and they passed by it (regularly even) wouldn’t they have noticed the unusual abundance of sulfur and salt in the area? In fact the entire reason why the area is typically identified with Sodom is because of the high amounts sulfur and salt deposits in the area (in fact many biblical scholars would argue that part of the reason why the Genesis Sodom story was originally written was to explain the geographic features of the area). So it would seem strange to me that people who had visited the southern Dead Sea area and identified it with the Sodom story would just forget or omit the parts of the story involving sulfur and salt. So maybe instead the Quranic author was just drawing on a local Arabian tradition that said a different location was where the city/town of Lot was and this location was much closer to Mecca. We know from Q 11:89 that the people of Lot were “not far” from Midian. So presumably the location of the Quranic town of the people of Lot was somewhere north of Mecca but south of Midian. Does this hypothesis seem plausible to you? I think we might be trying to impose too much of a biblical framework on the location here and we should consider the fact that the Quran can (and often does) contradict Biblical tradition. Anyways, I also agree with you that a lot of the vegetation in the Quran is exaggerated for theological reasons (Nicolai Sinai made this point recently on Reddit) but I also noticed that Q 14:37 seems to say that the area of Mecca doesn’t have any cultivation. This might actually indicate that the Quran itself says there was not much farming going on there but I am not sure if my interpretation is correct. Let me know what you think.

I agree with you, Henri, that we are unwise to impose the biblical framework on the Qur’an. Often the Qur’an treats biblical stories quite differently to make its own unique points. I also agree that the Petra hypothesis creates more problems than it solves. Petra isn’t close enough to the south end of the Dead Sea for it to fit the description if we interpret the text literally. I hadn’t thought of associating the text with an Arabian location for Sodom, but that is possible too.

The issue of course is not Petra but Mecca… The Petra hypothesis is flawed but the problem remains and you are certainly less interested in solving the real historical problems with Mecca (or, in fact, not at all interested, really). You are merely pressing your own preference based on . . . you’re gut feelings? The reason we should accept the traditions as they are is that . . . Muslims exaggerate? That they are bad at directions? It is tantamount to 19th century (or even some current) arguments against the evolution theory when people insisted on the truth of Bible’s declaration that God created the world in seven days . . and defending it by saying, “nowhere in the Bible does it say how long ‘seven days’ are” so . . .

Hi Cad

Thanks for your comment. I’m not sure I understand all of your questions, especially the ones that seem to be statements more than questions. But the task of the ancient historian isn’t to prove what happened. That’s never really possible. All we can do is demonstrate which explanation is most likely true in that it takes account of the evidence better than any other explanation.

Because Muslims have always cherished Muhammad’s memory, it only makes sense that they’d rehearse details of what he said and did to keep his memory alive. And we have every reason to believe that they did that–that’s what the hadith are all about. Are ALL of the hadith reliable? No, Muslims have known that from the first. But that doesn’t mean we throw ALL of them out. It only means that we need to wrestle with what is most likely true in the hadith and what is most likely false.

With that in mind, I can’t see any reason to throw out all of the hadith that speak of Mecca or to suppose they were all edited to say Mecca instead of some other place. No, what seems most likely is that those hadiths that give over-the-top descriptions of Mecca are exaggerations. But to say it wasn’t Mecca doesn’t make sense to me for many reasons. For one, why would they have moved the Kaaba to Mecca, of all places? Nabatea is certainly a far more accessible place to make your religion’s central shrine and site of pilgrimage. I might be able to understand why Muslims would move their sacred shrine from Mecca to Nabatea, but not the other way around.

It makes far more sense to me that Muhammad started out in Mecca and then Islamic rule expanded so far beyond Mecca that we now wonder why Mecca was made the central shrine. What’s changed isn’t the location of the Kaaba, but rather Mecca’s location relative to the Muslim world’s centers of power. That is, Mecca started out being fairly central to Muhammad’s community, but it’s no longer central, demographically speaking.

I don’t know if that helps you any, but contrary to what you may think, I am interested in solving historical problems. Just because I may disagree with you doesn’t mean I’m interested only in telling you what feels best to me. But again, let’s be clear about the limits of historical study. You and I don’t get to PROVE anything in ancient history. We only demonstrate (if we can) which explanation fits the evidence best, which is what I tried to do in my article.

Mark

In the middle of Petra / Mecca arguments. One forget to ask a simple question… Muslim in general bury there dead. where are all the 1000’s of Muslim graves in Petra?

Don’t tell me, Abd-al-Malik and his team dug up all those graves and shifted them to Mecca.

Wow great article. I like Tom Holland but I think he might be wrong on this issue. I do have one question though about the Quranic data on agriculture: If olives can’t be grown anywhere in the Hijaz, what do you think is the best explanation for them showing up in the Quran? Do you think it might be evidence that Muhammad’s rule had gotten to or near Nabatea-Palestine and/or Yemen by the time those verses were composed?

Good question, Henri. Chronologically, the first and last appearances of olive trees/olives in the Qur’an are Q 95:1 (Early Meccan) and Q 24:35 (Medinan). They are both quite general, simply attesting to an awareness of olives and their oil’s use in lamps. The references that raise more questions are Q 16:11 and Q 6:141, which both seem to suggest that some of Muhammad’s hearers either grew olives or came from regions where they were grown.

You ask if the explanation lies in Islam’s having spread to Nabatea/Palestine or Yemen when those verses were given. Perhaps, but Suras 16 and 6 are both from Muhammad’s Late Meccan period, and we aren’t aware of Islam’s spread to either of those regions that early. However, Muhammad seems to have called people from across the Arabian Peninsula and beyond to become Muslims from fairly early on. That is, he saw his messages as calling people from well beyond the Hijaz to submit to God. In that sense, it seems reasonable that he might address Yemeni or Palestinian/Syrian traders, given that Mecca was near the trade route running from Yemen to Gaza/Syria.

There is far too much in these comments to read, so I have a simple question: since idols are repugnant to Islam, and since Mohammed is said to have caused those in and around the Ka’aba to be destroyed, would he have left the statues carved in the cliffs of Petra untouched?

You make a good point, Harvey. The twin Greek gods Castor and Pollux, protecting travelers, are carved near the bottom of Petra’s “Treasury.” There is also a female figure, believed to be Isis-Tyche, a goddess of good fortune, carved on the tholos. This is hardly in accord with the anti-idolatry stance we find in the Qur’an.

Hi, I am confused by this topic. I was reading about the war between the Byzantine Empire and the Sassanid Persian Empire, as ancient wars are my interest, and found myself here. The theory about Mecca being in Petra is something new to me. I know that the author is against the theory, but how did this theory even gain traction?

If Mecca was originally in Petra, wouldn’t it be under Byzantine rule as it is a provincial capital of the Empire and the Muslims should be Byzantine citizens? How would Mecca be impacted by the Byzantine-Sassanid War which swept through Jerusalem to Petra and all the way to Egypt? Also, since the Muslims conquered Mecca between 629-630 and the Byzantine Empire defeated the Persian Empire in 628, why was there no response from the Byzantine Empire to the Muslims. A foreign Arabic army with its former citizens from Medina just invaded and conquered their provincial capital and they did nothing about it? That seems strange. It would also change the historical account of the Byzantine-Arabic War that comes after in terms of where the battle started and the movement of armies between the 2 empires.

Also, we have no accounts of a war between the Byzantine Empire and the Arabic tribes during the Byzantine-Sassanid War (i.e. the battle of the trench, etc.) and no account of any religious upheaval in the Petra community due to the rise of Islam during this time, assuming that Mecca was originally in Petra.

I’m coming from the angle of the wars and their impact. The Petra theory would mean that we have to revisit both wars if it is true. The evidence from Dan Gibson does not seem to consider this aspect. I’d appreciate it if any proponents of the Mecca-was-originally-in-Petra theory can explain it in such a way that they take into account both of these wars.

Thanks, Hzulkar. You raise an interesting question. While I’m no proponent of the Petra theory, the answer lies in the way its proponents dismiss the earliest Muslim accounts of Islam’s origins as either highly inaccurate or altogether contrived. That is, they dismiss the idea that Islam was centered in Medina in 629-30 and conquered Mecca (in KSA) during that period. Rather, Dan Gibson says Islam was centered in Petra and moved to Mecca (in KSA) much later. Some proponents of the theory that Islam originated in Nabatea claim that Islam didn’t really exist until the 690s. In my next article I plan to spell out what I believe happened and how it relates to the Byzantine-Sasanian War you refer to.

Mark Anderson, u bring no argument only denial

Thanks for your criticism, Pavel. I accept your implied challenge and will make presenting the positive case for Mecca as Islam’s birthplace my next project.

The main issue here is not whether Petra is the right place but rather if Mecca is not. There is plenty of evidence pointing to how impossible Mecca is as the birthplace of Islam. Mr Anderson refers to many of these points and tries to construct theories why Mecca could still be the place mentioned in Qur’an. Some of them are rather amusing like the claim that the reason why we do not have any archeological evidence from Mecca is due to constructions projects. Could it be that they already know that there is nothing to be found? What would happen to a Saudi archaeologist who says that Mecca is not the right place for Hajj?

Mr Anderson’s reasoning reminds me of how people were trying to explain the movements of planets with the earth in the center: it can be done, but becomes extremely complicated. Whereas, placing sun in the middle solves the problem. In the same way, placing Muhammad’s birthplace somewhere else explains all the conflicting facts. I do not expect Muslims to accept that their Hajj goes to wrong place. I do however expect that historians who claim that Muhammad was born in Mecca also provide some evidence for that, other than that it is what contemporary Muslims believe.

Partly in response to your criticism, I plan to write an article presenting the evidence from the other direction–that is, to explain positively why Mecca makes sense. According to Christopher Melchert, professor of Arabic language and Islamic history at Oxford University, the current consensus among Western scholars of Islamic history is that Islam did indeed originate in Mecca. That surely wouldn’t be true if the case for Islam’s Meccan origins was as far-fetched as you think it is, Eero.

Sometimes highly complex problems require complex explanations. Simplistic explanation may satisfy those unaware of the complexity. Locating Islam’s origins outside of the Arabian peninsula seems to solve the problems, but it invariably creates more problems than it solves. You say that “placing Muhammad’s birthplace somewhere else explains all the conflicting facts.” Locating it in Petra certainly doesn’t do that. So I wonder what other location you have in mind.

Thanks very much, Patrick, for responding to my requests. I’ve responded (in italics) to the points you make.

1. “I would like to note here that I did not write Seeing Islam in order to refute Hagarism, which some students have told me is a commonly held opinion, but rather to penetrate deeper into the question of Islam’s origins, with the idea that I was going to find out the Truth of the matter (strange as that seems to my now cynical/wiser self), but certainly with no sense that Hagarism was wrong.” Hoyland, https://www.academia.edu/42868584/The_Identity_of_the_Arabian_Conquerors_of_the_Seventh-Century_Middle_East

I’m surprised, Patrick, that you take Hoyland’s statement to mean that he does not think that Hagarism’s hypothesis is wrong. You read far too much into it. All he is saying is that he approached the Islamic origins question with an open mind and without specifically setting out to prove it wrong. No one can read Seeing Islam and think he approves of Hagarism, which even its own authors disowned.

2. This what my first [unpublished] comment said “The 5th century Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi also places a Makka in the country of Pharan. Since the islamic legend did not exist in his time, the argument you used to gainsay Artsruni does not work.” In addition to Ardsruni (10th century) you can add Vartan Pardserpertsi (13th century) among the historians who do the same. Ref: Marie Brosset, Collection d’Historiens Arméniens : Histoire des Ardzrouni,, Imprimerie de l’Académie impériale des Sciences, 1874, 665 p.

Edouard Dulaurier, Recherches sur la Chronologie arménienne : Technique et Histoire, Imprimerie impériale, 1859, 469 p.

M. J. Saint-Martin, Mémoires historiques et géographiques sur l’Arménie : vol. 2, Imprimerie royale, 1819, 533 p.

Without library access (due to Covid restrictions), I cannot check your claim regarding Movses Khorenatsi. So for now, I’ll take your word for it, Patrick. I may be wrong in my explanation for Artsruni’s mislocation of Mecca. Perhaps he was confused by something Movses Khorenatsi said. In any case, your last comment claimed that there were other Armenian “historians” (plural) before Artsuni who identified Petra with Mecca. Now you name just one previous historian, Khorenatsi, plus another in the 13th century. This sort of overstatement doesn’t strengthen your case.

3. I did not mention scholars who “accept the Petra hypothesis” but scholars who reject the South Arabian hypothesis (which you turned into “scholars who reject the Arabian location”!). You already acknowledge they exist when you say “Patricia Crone was the first to say Islam originated in the region of Petra. There are a number of other scholars who agree with her.” Did I misunderstand or should I have assumed from your “revisionists” tag that you don’t count them among the credible scholars? To those mentioned in the Wikipedia article, you can add Alphonse-Louis de Prémare, Edouard-Marie Gallez, Robert Kerr, Claude Gilliot, and others I can dig if necessary.

I don’t mean to be pedantic, Patrick, but in your previous comment, you wrote: “It is false to claim that Islamic scholars reject the Petra hypothesis.” As you may know, there’s a difference between “Islamic scholars” and “Islamics scholars,” the former meaning Muslim scholars, the latter meaning scholars of whatever persuasion who study Islam. So I assumed you meant Muslim scholars. Now it seems you meant Islamics scholars. I’m well aware that some non-Muslim scholars locate Islam’s origin in Nabatea or elsewhere in the Fertile Crescent.

I notice that you sidestepped my 3rd request, however, which was for an explanation as to how you determined that a majority of scholars “reject the South Arabian hypothesis,” as you call it. I take that to mean that you did no study, but have only drawn that conclusion because it’s what you want to believe.

I have no political or religious agenda here. In dismissing Gibson, you may have thought you were attacking a polemical position (as used by Jay Smith?) and may have been surprised by the number of Muslims who actually agree with Gibson, who has no adversarial relationship with Muslims, contrary to what King claimed. Indeed not only is Gibson receiving contributions from people in the Muslim world but he has been endorsed by some in the Coranist milieu. King’s position that the early qiblas had nothing to do with the direction of al-masjid al-haram but with archaeogeography is much more unaceptable to Muslims than Gibson’s position.

I’d be happy to know if you have any sources to support your last statement, which I find highly doubtful.

I noticed in your answers you tend to point anecdotal mistakes while ignoring the stronger points. I certainly do not wish to dispute about minutiae. I happily spent time to satisfy your requests and back them with references. But it is not my intention to spend time listing every detail or assumption which I think is wrong in your article. I am more interested in any responses to the double tradition reflected in the Armenian historians, Ibn al-Rawandi in the Kitab al-Zumurrud, the Qarmatians, and many other elements like the hajj, Kaaba of Petra and the Kaaba of Mecca, the cult of the three daughters of Allah in these two places, the toponymic duplication of placenames in North Arabia and the Hedjaz, the duplication of famous tombs. Patricia Crone did not invent the double tradition. It was there in the record all along. [I take it that you mean it was there all along waiting for someone to find it. Because it certainly wasn’t put forward as a theory before the 20th century.] Until this can be properly explained, we are better keeping a skeptical mind toward the traditional version.

You ask for my response to a number of points you believe build a strong case for what you call the “double tradition.” I’ll do that in a separate comment.

Before I respond to the points you consider substantive, let me say that I don’t automatically assume that any sort of revision of the traditional origins narrative is evil. But I think it’s wrong to automatically assume that the traditional account is false just because it’s traditional. I just try to look at the evidence for each. I have another article I’m working on which will hopefully build a stronger case for the traditional view.

In any case, here are my responses to the points you consider substantive:

I can understand why you would think that the fact that there was a kaaba at Petra seems to be evidence that the Muslim Kaaba was originally there. But there were other pagan cube-shaped shrines (kaabas) elsewhere in the Arabian peninsula. There were other black stones (than the one in Mecca) venerated by pagan Arabs also. Muslims view the fact that Islam had no monopoly on either cube-shaped kaabas or black stones as a case of the pagans copying the true religion, Islam, while non-Muslims read it the other way, as Muhammad’s incorporating pagan practices into his religion. Either way, the fact that there are the ruins of a kaaba at Petra says nothing about its being the original site of Islam’s central shrine. Likewise, the daughters of Allah were worshiped in various locations throughout the region. So the fact that they were worshiped at Petra doesn’t prove anything.

I find the duplication of place names in North Arabia and the Hijaz very unconvincing. As you may know, a Lebanese historian in the 1980s did the very same thing with biblical place names, attempting to use toponymy to prove that the promised land of the Bible was actually in southwest Arabia (near Mecca), despite all the other evidence to the contrary. (The fact that he published his book around the time of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon suggests that he was trying not just to sort out a historical issue, but also to delegitimize Israel’s claims to Palestine.)

You mention an epigraph dating the Kaaba’s building to after 78 AH. Which epigraph are you referring to, does it give a specific date, and what source do you have for that? I assume the epigraph refers to one of the many times the Kaaba was rebuilt.

You mention that al-Rawandi said Mecca was just one day’s distance from Jerusalem. But Petra is over 200 km from Jerusalem, which is much farther than even the fastest horse can go in a day. Without having seen the context of al-Rawandi’s remark, I assume he was making an understatement for literary effect, like arguing that your British friend should come and visit you in Rome by saying, “London is just a hop, skip and a jump from Rome.” Anyone reading those words would know they’re not to be taken literally. If al-Rawandi had given a specific distance in miles (Arabic, mil), we might have more reason to take him literally.

Finally, you mention the Qarmatians’ disregard for pilgrimage. But on the one hand, we know that qibla and pilgrimage has been important to standard Muslims from the very first. And on the other hand, the Qarmatians never disputed that Islam originated in the Hijaz or complained that the Kaaba, Black Stone or “Mecca” had been wrongly “relocated” there. So how does their disregard for pilgrimage have anything to do with the question of origins? When you bring up a point like that for no apparent reason, it looks like you’re just throwing up dust to make it hard for people to see the evidence in front of them.

Second time I am posting this. Artsruni is not the only scholar to identify Petra with Makka, it was already done before the start of Islam by previous Armenian historians. There were Arabs from the muslim world who complained the south Arabian Mecca was not the right one. Al-Rawandi said Mecca was just at a one-day travel distance from Jerusalem. Qarmatians also considered pilgrimage to Mecca a superstition. Pilgrimage to Petra continued unabated until the mid-1980s when the Jordanian stopped it because they considered it a superstition. The two competing Meccas is not an invention of the “revisionists”. It is a more than a thousand year old problem. It is false to claim that Islamic scholars reject the Petra hypothesis. A majority of those who study the question of geographic origins actuall reject the South Arabic hypothesis. Those who accept the South Arabic hypothesis are those who do not concern themselves with origins. I see you are quting Hoyland. Do you know that Hoyland has written that he does not think the Hagarism hypothesis is wrong? You also have the epigraph which dates the building of the Kaaba to 78 after hegira. And there is the Mark Durie identification of Quranic Arabic with Nabatean Arabic. And Nabateans are the inventors of Arabic script and Arabic tradition has customarily (wrongly?) identified the birth of Arabic script with the Quran, which again ties the Quran with Nabateans. And I have not mentioned the qiblas or the fact that pilgrimage used to be associated with the place of the black stone. You need to rely on more than non-existent consensus among scholars and Muslims. When you can account for the double tradition and all the discrepancies, you can state with confidence that Petra is not Mecca. But only then.

Thanks for your comment, Patrick. Due to the religious sectarianism involved, I get more comments on my Petra article than I can publish without turning my website into an All-about-Petra website, which I don’t want to happen.

You say the majority of those who study the question of Islam’s geographic origins reject its Arabian location. That’s a broad claim to make. Can you tell me how you arrived at that conclusion?

You mention Mark Durie’s hypothesis re qur’anic Arabic. You’ll be disappointed to know that Mark Durie recently wrote me to say–and I quote–“I am not really happy with that paper I showed you, and want to rewrite the part concerning the Arabic dialect.” He went on to say that scholars in the field had pointed out its weaknesses. That was from Durie himself. I had been planning to include his hypothesis on my website as one unanswered question. But on hearing that, I naturally decided to hold off till he feels he’s answered the criticisms leveled at his hypothesis. Until he’s done that, we can’t possibly decide on its value.

I’d be happy to discuss the topic of Petra/Mecca with you further if you could first supply me with the following:

1. A source to back up your statement that Robert Hoyland doesn’t think Hagarism is wrong

2. The names of the Armenian historians before Artsruni who identified Petra with Mecca

3. The names of any credible Islamic scholars who accept the Petra hypothesis

I’m tempted to respond to a number of your points, Patrick. But before I do, I need to know that I’m not just going to get into a shouting match with you. The fact that you submitted your comment twice tells me you take this issue very seriously. If you do and would like to discuss it further, please start by supplying me with the three things I requested above.

I’m not sure what your interest in the topic is. I’m not a Muslim myself and have no vested interest in the issue, one way or another. I’m simply trying to determine what the preponderance of solid–not flaky–evidence is. I’m definitely not interested in stoking the flames of anti-Islamic sentiment. That’s not what this website is about at all.

You are to be praised for your balanced contribution as a disinterested non-Muslim, Mark.

One point which the revisionist camp are completely blind to is the oral testimony of the majority of an entire community (known technically in Arabic as Mutawatir = multiple chains of oral transmission or narration) who, in the white heat of their religiosity, would have striven to faithfully and reliably hand down key information from one generation to the next. This applies to both the Qur’an and the manifestly well known aspects of the new religion’s praxis. To suggest, therefore, the Qur’an has not been preserved (despite its transmission by hundreds if not thousands of its most sincere, dedicated and earliest memorisers) and that the Muslims did not know the locus of their prayer as well as the pilgrimage simply defies all reason and common sense.

The only explanation for this ardently deliberate oversight is a rabidly illogical anti-Islam scepticism (i.e. an ideological position) the likes of which its originators fail to apply to their own, very much less well attested, tradition and norms.

The irrigation system was crippled, yes, but – from what I have read – not wholly destroyed. Dan Gibson says that it was destroyed in 713 by an earthquake, which needs corroboration. However, there are at least the tracts from the last years of the 6th century, and the probable fact of Muhammad’s father working the soil. So Muhammad may well have grown into manhood in Petra.

Regarding the nomenclature (islam and muslims), there seems to have been no such thing in the years after Muhammad’s death. The Arabs who took Jersusalem did not use the words; people at first thought they were some sort of jews. By the time of the Dome of the rock, the canon was thoroughly established.

A very strange thing that the quran mentions places close to Petra 50-60 times, but never Petra itself. The rub may be that, since Mecca already was the Place, the committee putting the quran together redacted it so as not to confuse the masses. And don’t say that the early muslims never would stoop so low – no one knows.

To me, the fact that we have no extra-qur’anic evidence that Muhammad’s faith was called Islam before Abd al-Malik’s time isn’t all that remarkable. It’s akin to the fact that one of the last things most authors do when writing a book is give it a title. All or most of the content is usually there before the title goes on it.

The Qur’an does mention Petra once, as I said in my article.

You seem to connect Muhammad’s father’s working the soil with his living in Petra. But that could just as easily point to his living in Medina.

There’s a reason, Magnus, why no major Islamics scholar takes the idea of Petra’s having been named Mecca seriously. It’s really asking a lot for us to base so radical an idea on the words of a single writer, writing centuries later, a man who specialized in Armenian history and only mentioned Muhammad in passing. Is it really likely that Thomas Artsruni was the only historian ever to know about the secret name change? Most scholars would agree that it’s far more likely that Thomas was simply mistaken when he located Muhammad in Arabia Petraea Paran.

Well, Mark, you know your stuff. I am finalizing an elementary lecture called “Muslims and islam”. Thinking about when islam jelled, that is, say, up until 691, what do you say about the role of Abd-al-Malik in that process?

It seems to me that calling the quran’s gushing descriptions of arid Mecca hyperbolic is, if not disingenuous, at least not fair. The similarities with Petra are too many.

Thanks for the comment, Magnus.

If we assume that everything in the Qur’an—or even just in its Meccan suras–is about Mecca, then you’re quite right: we have a big problem. Because Mecca itself is far too hot to sustain any agriculture beyond very limited animal grazing.

But the fact that Muhammad’s community ended up in Medina suggests that the qur’anic messages weren’t just addressed to the people of Mecca. Those messages most likely always had a larger, regional audience in view.

I see no reason to doubt what the Muslim tradition says about Muhammad’s struggles to find a safe home for his community in his early preaching career. According to tradition, one place he went to seek refuge was Ta’if, which is relatively close to Mecca and had lots of agriculture. Though the people of Ta’if didn’t welcome him, that doesn’t affect my point, that the Qur’an likely refers to more than just Mecca. Indeed, if its concern was limited solely to Mecca, then it would be fair to say that Muhammad had extremely small ambitions. I wonder, why should we think that of him?

Even if we just include Medina in his audience, Medina had considerable agriculture. And on either end of Western Arabia’s overland trade route, Yemen and Gaza both had all the agriculture needed to account for the lush descriptions we find in the Qur’an.

I think you have a similar problem if you go with the idea of Petra as Muhammad’s initial location. If you’ve been to Petra, you’ll know that it’s not surrounded by lush agricultural land. Far from it! What rain it receives-—19.3 cm. (7.6 in.) annually—-often comes with flash floods, meaning that it’s gone almost as fast as it comes. The early Nabataeans controlled Petra’s erratic rainfall by the use of dams, cisterns and water conduits. But Petra’s vital water management system was crippled by an earthquake in 363 CE. So I don’t see how the Qur’an’s descriptions of lush agriculture would fit Petra during Muhammad’s lifetime.

You asked about Abd al-Malik’s role. Some aspects of Islam, now thought by many to be original, clearly developed during Islam’s early centuries. Most of those aspects are reflected in the hadith, not the Qur’an. But there’s good reason to take the Qur’an as representing what Muhammad left his community when he died. We know that the Qur’an has variants, just like every other ancient scripture. But we have yet to see solid proof that those variants have changed the text significantly.

So I accept that what we have in the Qur’an represents the earliest forms of Islam. Of course, that raises various interpretive questions. But I think we can at least say that the Qur’an shines a powerful spotlight on Muhammad, as prophet. So we don’t have to look to Abd al-Malik—as seen in his coinage, etc.—as initiating that. Rather, I view him as emphasizing the distinctives that were already there to try to set his community apart from Christians and Jews in Syria and beyond.

So. Mecca archeological finds. Where are they?

I wonder, Martin, if you missed the following in my article above:

“Due to the Saudi Arabian government’s mortal dread of shirk, or polytheism, it has strictly forbidden all archaeological study of Mecca’s historic sites, lest it lead to relic worship. Indeed, the Saudis seem determined virtually to obliterate the city’s archaeological record in their rush to ring the Kaaba with skyscrapers. An estimated 95% of Mecca’s historic buildings have been demolished to allow for this building spree. Any remaining historic sites are treated with a combination of fear, contempt and scholarly avoidance, lest they be idolized. Unfortunately, this leaves us with no archaeological evidence either for or against Mecca’s being Islam’s birthplace.”

Maybe the climate of the region (Mecca) was different from what it is now and this could prove that Mecca could have matched its descriptions in the early period of Islam’s emergence.

Actually, one thing we know with real certainty is that the region’s climate hasn’t changed significantly since well before Muhammad’s time (apart from very recent global warming). Archeologists, anthropologists, biologists and geographers all agree on that.

Petraea Paran was Roman description of this region that was known as Al Raqim to the Jews and Nabateans before the Roman invasion. Petra (originally known as Becca…vale of tears) refers to the valley between the mountains of Safa and Marwa…not the two 10-foot-high rocks within the Kaaba mosque in Saudi Mecca. In 622 CE, Mohammad fled 400 km south to Medina.

The foregoing is proven by the history of the battle of the trench in Madina in 629 CE. It is recorded that defenders dug the trench between the hills North of Madina. Why would they do that if invaders came from the south?

In 683 CE, during the second civil war, Ummayad forces besieged Abdullah bin Zubayr in Mecca. Word then came of the death of Caliph Yazid in Damascus. The siege was lifted and the entire Ummayad army marched off north to attend the inauguration of the new Caliph. But they returned in 3 months to renew the siege of Mecca. That is only possible if Petra was the old Mecca. The current Saudi Mecca is four times further south; i,e., 2,000 kilometers from Damascus. A fully laden slow-moving army with baggage trains and retinues could not march the 4,000 km return journey in under 7-8 months.

It is pathetic to argue that Muslim Dark Ages between 632-691 CE are to blame for the absence of any written record because they were either illiterate or had no time to write as they went about conquering a quarter of the known world. More disturbing still is the fact that earliest scraps of Quranic manuscripts date to mid-late 8th century. In fact, the earliest complete Quran comes from the 12th century. Clearly then, Islam, Quran, Sirat, Hadith, and commentaries remained works in progress for 200-300 years after the Prophet of Islam. And, it all began with Abdel Malik and his son Walid circa 691-712 CE. But the process was not complete till well into the Abbasid Caliphate.

Thanks for your comments, Mian. Let me respond to a few of the points you make. First, I’d be very interested to know if you have any reputable source for saying that Petra was originally known as Becca. So far as I know, Dan Gibson makes that claim as pure conjecture. On what basis do you make that claim?

You asked why the Muslims dug a ditch on Medina’s northern side to defend against Meccans coming from the south. Because the northern side was the only one unprotected from cavalry attack by rocky terrain and trees.

I’m not sure which military expedition to Mecca you refer to. The 6-month siege of Mecca ended with Abdullah ibn Zubayr’s death in 682.

Please note that the Arabs weren’t entirely illiterate during the 7th century, but their culture was oral. The Qur’an played a major role in Arab culture’s gradual shift from being oral (where most things weren’t written down) to being literate (where many more things were). That shift played out over the eighth and ninth centuries. Before it, the Arabs didn’t bother to put lots of things—history, for example—down in writing.

You’re mistaken to think we have no qur’anic mss before the 8th century. The Sana’a palimpsests have been reliably dated to the mid-7th century. Until the discovery of those manuscripts in the 1970s, it was possible to claim that the Qur’an evolved over a century or two, beginning with the reign of Abdel Malik. The Sana’a manuscripts makes the traditional dating of the Qur’an very believable.

Also you mentioned that Quran reached the Yemen during early period, do you forget that Othman Caliphate reached to Yemen, Egypt, Iran and Syria. Othman who initiated the compilation of Quran and sent copies to different provinces. Where Othman was living? Damascus. All of the capitals of Caliphate were in Syria and Iraq.

I think you are influenced by hardcore believers of Islam. By the way there is no mention of Mecca in Quran, it is Becca, in Nabatean it was for weeping place. Petra was because it was demolished due to earthquake multiple times.

I think it’s much more reasonable that “Becca” in Q 3:96 is another name for Mecca than that it refers to Petra. I accept that you don’t agree. But you’re mistaken to say that Mecca isn’t mentioned in the Qur’an. It’s mentioned by name in Q 48:24. The Qur’an doesn’t mention Petra by name at all.

Even supposing that Becca means place of weeping, that doesn’t tell us Petra was the place of weeping—unless you’ve already decided it was.

Saurabh, we’re not just talking about “hardcore” Muslims, whatever you mean by that. All Muslims accept that Mecca is where the Kaaba was located in Muhammad’s day. And yes, the fact that all Muslims accept this is central to my argument that changing the direction Muslims face in prayer from Petra to Mecca wouldn’t have happened without Muslims knowing it and keeping the memory of it alive in their oral traditions.

We humans aren’t very good at covering our tracks when we try to do things secretly. And the more people there are who know a secret, the less chance that we’ll succeed in keeping it secret. If the entire Muslim community actually made a major move without anyone ever talking about it, then they deserve a prize for keeping it secret until Patricia Crone, Tom Holland and others finally discovered it. To me, it makes far more sense that the traditions simply exaggerate the stories about Mecca’s economic importance, possibly even to the point of creating an economic profile for the town that Muhammad would barely have recognized.

Saudi people have understood that the Mecca was not the place where Muhammad born and that’s why they are demolishing everything in Mecca.

By the way, do you remember Muhammad visited Jerusalem many times, once even in single night, where should be Mecca to make this possible?

Mecca was off the trade route, geographically, it lies beyond a high plateau. Only fools will try that path for trade.

Arabic language was originated from Aramic, where aramic was spoken?

Nabatean were under Roman Empire and hence they were trained soldiers. People in Medina who never fought a war would conquer Arabia and Syria.

The mosques for first 100 years were facing towards Petra and then started moving. It was easy for Caliphate to change this as they hold the status of second only god.

Your research is poor and biased.

The geography mentioned in Quran more fitting with Petra than Mecca.

Yes, as Patricia Crone has pointed out, Mecca was a very unlikely place from which to build a trading empire. But the stories about Mecca’s importance in trade aren’t in the Qur’an. They’re based on tradition, which is much later and, I believe, really embellished. Muslims have always known that not all of the hadith (traditions) are reliable. I think most of what they say about Meccan trade is greatly exaggerated. So just because I accept that the Kaaba was in Mecca, doesn’t mean I think Mecca was a major metropolis in the region.

The Qur’an also reached china in 628 AD (the main mosque of Guangzhou) via trade routes that the Arabs maintained back in those days. So saying and I quote, “And Yemen would not have been as strategically important to an army from Petra in the Fertile Crescent, as one from Mecca/Medina” -end quote, neglects to face the fact that Yemen was on a trade route.

Saying that Qur’an found its way to Yemen early thus implying that Yemen was close to the Qur’ans’ place of origin/birth (MECCA) is entirely up to speculation.

Thanks for your comment, Mohamad. Yes, I admit that my suggestion that the Qur’an reached Yemen early because of its proximity to Mecca/Medina is not based on hard evidence to that effect. The problem is that we don’t have such evidence. We have no written evidence from Islam’s first 2 centuries on the location of the Kaaba, other than the Qur’an’s mention of Mecca (but not Petra).

From my perspective, Yemen mattered because of its proximity to Mecca/Medina. You feel it was important because it was on a trade route. That is, our view of Islam’s early arrival in Yemen fits with our different perspectives on Islam’s birthplace. But neither your understanding of that point nor mine is going to convince the other of the rightness of our overall view.

By the way, the earliest date I’ve seen for the building of the first Guangzhou Mosque is actually in the early 700s, not 628 as you say.

A great reply to Holland and Gibson. Allhamdulillah.

Let’s keep in mind the fact that Islam, Muslim, Mohamed and his prophethood finds no mention in any non-Arab account till the Caliphate of Abdel Malik (685-705 CE). Early Christian and Jewish sources mention that Arab invaders who erupted out of the Southern deserts around 634-36 CE called themselves Hagarines, Saracens, or Ishmaelites…not Mohammedans or Muslims with a book called the Quran.

Islam, with its Quran, Hadith, and Sir-at are products of mid-late 8th to 10th centuries CE with Abdel Malik and his son being Principal inventors of the faith as we know it today.

You’re right to say that no non-Arab account mentions Muhammad, Islam or Muslim by name until Abdel Malik’s reign. But I can’t see why you’d take that to mean that Abdel Malik and his son invented Islam. Islam definitely seems to have taken on more definition during his reign.

You seem to be arguing from silence, saying that the absence of something in the written record–especially the unsympathetic (i.e., non-Arab) written record–means it never existed. But the written record gives us only a tiny fraction of what happened in the seventh century CE. I believe Robert Hoyland says historians only recover 1% of what existed. So the fact that we haven’t yet found written evidence for something proves only that we haven’t yet found written evidence for it. And relying entirely on unsympathetic (non-Muslim) sources opens you up to just as much bias and, hence, distortion as relying only on sympathetic (Muslim) sources.

It seems you may be basing your ideas on Crone & Cook’s long discredited book Hagarism. Crone & Cook quickly renounced the theory propounded by the book, which predated the classification of the Sanaa manuscript by a few years. That event changed a great deal about what we know of pre-Abdel Malik Islam since we now have indisputable proof that the Qur’an existed within a few decades of Muhammad’s death. We still have many questions about the early period. But we can piece enough together from all the sources to know that, while the Muslim faith seems to have taken on sharper definition under Abdel Malik, he was by no means its inventor.

You mention that the first Jewish and Christian sources speak of the Arabs coming out of the southern deserts. That doesn’t particularly point to Petra since anyone coming to Palestine from Mecca/Medina would also have come out of the southern deserts. We also know that the Qur’an had reached Yemen during the early period. And Yemen would not have been as strategically important to an army from Petra in the Fertile Crescent, as one from Mecca/Medina. So I believe the Sanaa Manuscript suggests that Islam’s origins were more southerly, in the Hijaz.

Mohammed and his first wife, the Uber-rich Siti Khadija, obviously not from Mecca.

Siti Khadija was a woman of great importance who wilded so much power, publicly and culturally, as she was the one who – according to traditionalist – proposed to the younger and handsome Mohammad to marry.

Can we imagine a Saudi woman did such thing 1300 years ago? They were just barely allowed to drive last year! But in Petra/Jordan? Of course. Petra was the center of the Eastern World in around 600-700 AD. It was the equivalent of today’s New York City.

Another hint was how the Musulman refer to Christians – Nisrani. Why? Because the historical Mohammed was a friend / student / protégée of a Nazorean Christians monk. Nazorean Christian monk was expelled from the Eastern Roman Empire after the first Council of Nicaea (Iznik), held in Turkey at the behest of Emperor Constantine around 330 AD. Why Nazorean was banned? Well, just like the follower of Bishop Arius, we refer to them as Arians (has nothing to do with ‘white race’), they didn’t acknowledge the divinity status of Jesus Christ in the concept Trinity……. Arian Christians and it’s brothers, including the Nazoreana, hang on for such a long time after this Council of Nevada, mainly in the region controlled by the Visigoths, Spain, North Africa, etc. and in the birth place of a Christianity, the Middle East.

The last evidence is still very clear: The Original Kiblat of Masjid Al-Aqsa (the Dome of the Rock) in Jerusalem, built around the 7th century, was facing Petra (South). Not Mecca (South East). One doesn’t need to be a historian or archaeologist to find this evidence. And then there is the “Mosque of the two Kiblats” mentioned in Dan Gibson’s documentary.

I appreciate your taking the time to write, Ibrahim. But you’re seriously misinformed on the importance of Petra in the Eastern World in the 7th century CE. By then, Petra had long since gone into decline. It was by no means the center of the Middle East. Also, the direction of Mecca from Jerusalem seems obvious to us now–in a world of accurate maps, airplanes and satellites. But the Dome of the Rock was built long before any of those things. Mecca’s direction was far less clear back then.

I’m sorry to say but Mecca in SA is deffinately not the origin of islam. Gibson is just one of dozen ‘scholars’ who thinks it is not in SA. It begun with Patricia Krone in the 70’s en even before that, some orientalists/revisionists (Wansbrough/Ibn Warraq etc) noticed that the language of the qur’an could not be from the Hidjaz but rather much north (Irak/Syria/Jordan). Even the qur’an itself testifies that the geographical scene could not be in today’s Mecca. Mecca in SA is garbage and it is no secret to ‘real’ scholars. I’m not saying it is Petra but it is more likely to be in that area than SA.

You’re right to say that Patricia Crone was the first to say Islam originated in the region of Petra. There are a number of other scholars who agree with her. The question of the Qur’an’s Arabic dialect is an interesting one. Linguist Mark Durie recently wrote a paper stating that the Qur’an’s dialect represents the Arabic spoken in the Nabatean region. I hope to engage with him on that in an updated version of my article. I would argue, though, that, if he’s right, it’s still highly unlikely that the entire Muslim community moved south to Mecca without any trace of that event in their collective memory. It would make far more sense to say that Muhammad originated in Nabatea. And that after the Medinans triumphed over the Meccans, the story of his Meccan origins arose to make him a “local son” and bring the Meccans on board. (That sort of thing is known to have been done in the ancient Middle East.) The people you refer to as “real scholars” will undoubtedly be discussing this for some years to come.

One more set of queries, besides earliest known mention on trade map n reference to Mecca (besides the Greek Ptolemy). Some revisionists also challenge timeline when Quran at earliest actually written down. From discussions by some higher critics like Jay Smith Christian evangelist, the evidence seems pretty overwhelming that there are many variations understandably found between even the earliest extent copies n many parts n phrasings.

Just in conclusion, the problem of tying lineages in Quran to Hebrew kings n prophets. The stories of Moses Solomon n David along with discussion from higher critics dating back last century’s beginning finding no evidence these characters could have ever existed? Most everyone knows not one trace (zero) any archaeological finds found after centuries of looking. Now along with current research of well known Israeli archaeologist, Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv Uni, his revisionist thesis now sees the true genesis of Hebrews being an amalgamation of nomadic hill tribes with low land Canaanite peoples.

* How ironic is that?(!!) The very Canaanites that receive such negative light in the Torah? Yet with the real n dated Amarna Letters between Canaanite Chieftans with Egyptian kings as overlords of Judea,here’s a thesis with greatest eveidence of being a reality. Since no mention of Hebrews has ever been found in any extent history outside of the the Torah. (only one very vague n questionable stele)

BEGINNING MONOTHEISM OF JUDAISM

Then considering any study real history shows this ancient monotheism of ‘Judaism’ as a monotheism really doesn’t come into existence until very late 6th century with returning orthodox believers circa Post Exile, with the prophet Ezra.

HEBREW BELIEF IN ETERNAL SOUL, HEAVEN, HELL & PARADISE

Until Cyrus the great liberated Babylon it turns out Before Cyrus the great liberated Babylon, Hebrews couldn’t even imagine an ‘Afterlife’ or Heaven/Paradise or an Eternal …the soul of man perished after 3days in Sheol.

Pretty important ideas one would think , the Jewish Virtual Library (under “the birth and evolution of Judaism”) states this clearly here:

“Absolutely none of these elements were present in Hebrew religion before the Exile. The evil in the world is solely the product of human actions—there is no “principle of evil” among the Hebrews before the Exile. The afterlife is simply a House of Dust called Sheol in which the soul lasts for only a brief time. There is no talk or conception of an end of time or history, or of a world beyond this one.”

The question of changes in the early qur’anic text is one I hope to address before too long.

Excellent discussion….One question of trade maps,either the Gibson or Holland ‘revisionists’ bring up Mecca not being noted on any trade map much later as u mentioned. Very much like to know who in the world are the real leading specialists in field of history such trade maps? Or which museums carry the most detailed information? At the beginning your covering an amazing lack of qur’anic evidence, the fact that the Qur’an itself names Mecca just once? Really?? That is simply astounding if true!!

Doesn’t this really set off some kind of alarm?

regards

I think one of the things we struggle to understand in the West is that the Qur’an is not a continuation of the sort of writings we find in the Bible. It’s very different. It is oral “oracular” speech primarily for a local audience. By oracular, I simply mean that Muhammad presented it as divinely revealed prophecies, given in the moment without any forethought or planning on his part. That being so, it typically doesn’t mention anything his audience knew about what he was saying. So, if a message he gave was about the sacred mosque down the street, he didn’t bother to say which city it was in. He didn’t need to because everyone present knew where they were and what he was referring to.

That explains why the qur’anic text seems so vague to us many centuries later. Its messages addressed specific local audiences. The Qur’an is very different from what we find in the Bible’s prophetic or historical writings in this regard. Its texts were composed to address a much larger audience–e.g., the Israelite community–than the qur’anic messages addressed.